The Folly Cove Designers

Virginia Lee Burton (1909-1968) was an American illustrator and children’s book author - best known for such classics The Little House (1942), Mike Mulligan and the Steam Shovel (1939), and Maybelle the Cable Car (1952). She wrote and illustrated these stories, and several other popular narratives for children in her cottage by the sea in a small town called Folly Cove located in Gloucester - a coastal town in Cape Ann, Massachusetts. While Burton was busy churning out mid-century American storybook classics and raising two boys, she was also operating a local design-craft business called The Folly Cove Designers (FCD). The collective, which consisted mostly of women, operated from 1938-1969 under the instruction and leadership of Burton. Together, they wrought intricate designs on linoleum blocks for textile printing - creating everyday household items both captivating and practical.

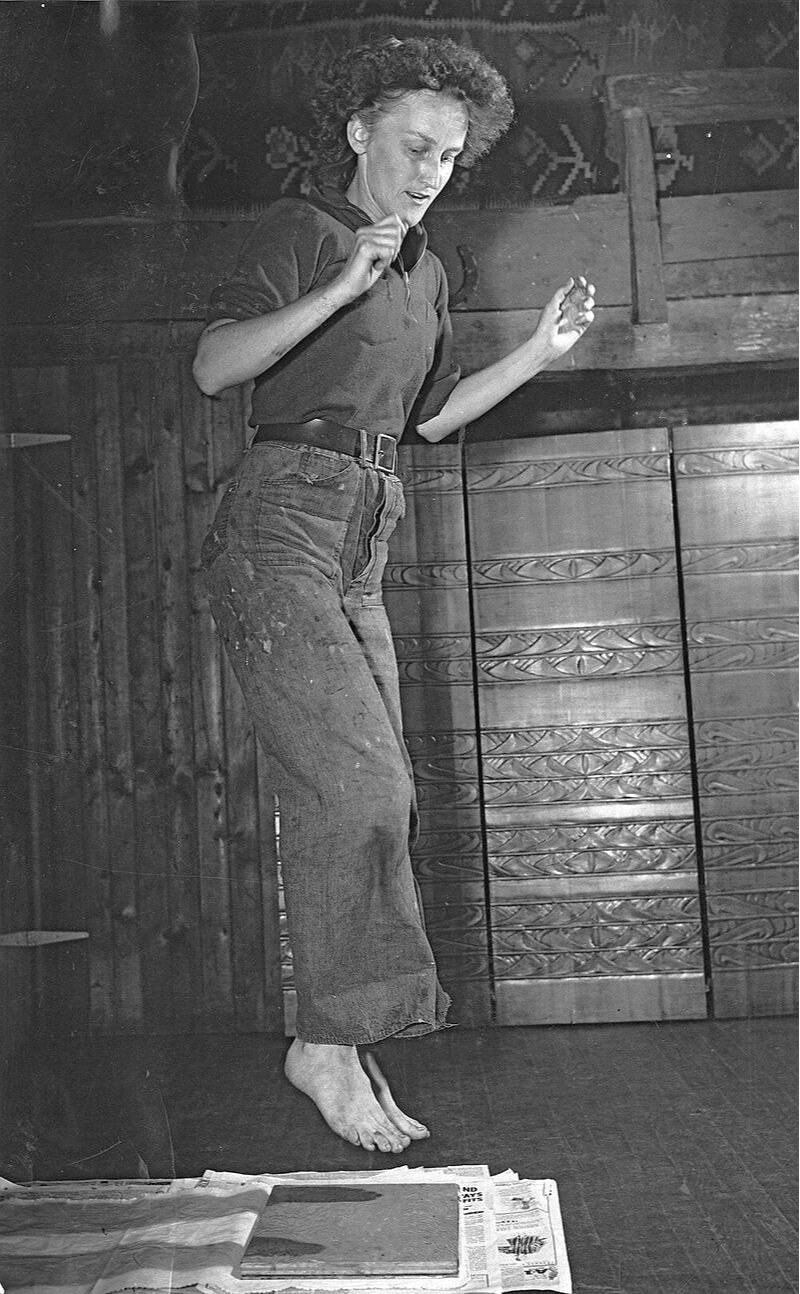

Virginia Lee Burton in her studio in Gloucester, MA. Source: Syracuse University Library

Mike Mulligan and his Steam Shovel, 1939

The Little House, 1942

Maybelle the Cable Car, 1952

Burton’s career as a children’s author and illustrator is prolific. Her literary success has overshadowed the unique story of her entrepreneurship and creative journey in design-craft, but the two go hand in hand. Burton possessed a rare talent in creating an intimate relationship between text and image. Her stories reflect the ethos that dominated the artistic movement sweeping through America at the time. Family, community, respect, and hard work were themes underscored by sentiments of nostalgia and melancholy about communal loss and individual uncertainty: consequences arising as a result of the depression years and America’s place in the industrial era. Her illustrations reflected precision and technique, lines of action providing movement and flow, and repetition and patterns offering rhythm and tempo. Burton’s aesthetic not only made her a pioneer in the evolution of the American picture book but was designed to have a powerful message that reflected her own ethos concerning life and work during mid-century America: resilience, reinvention, and reconnection to the social good.

In the early 20th century Folly Cove was home to a large number of immigrants including Greek, Italian, and Finnish who worked in the maritime industry as well as the Cape’s vast granite quarries. It was also a beacon for artists, including painters Winslow Homer and William Morris Hunt.

Burton moved to Folly Cove after she met and married renowned sculptor George Demetrios in Boston. They had two boys together, Aristides and Michael. Folly Cove was a place where Burton would finally find a stable footing with family and community, and her literary and artistic career would be ignited.

Image from left: Aristides, Burton, Michael, and George

“Now Jinnee was talking about the high price of paper needed for illustrating her first children’s book “Choo Choo,” and I thought if I asked neighbors and friends interested in design perhaps she could be our teacher and charge perhaps 50 cents to help pay for the paper. She accepted the teaching but refused the money.”

Folly Cove Designers, circa 1949. Source: Cape Ann Museum

The story of how the Folly Cove Designers was created is said to have begun with a simple barter agreement between Burton and her neighbor and best friend Aino Clarke. Clarke had admired curtains that were hanging in Burton’s home, and learned the author made them through block printing.

Wanting to learn this skill, Clarke sought to get enough members of the community to learn under Burton and pay her a nominal fee, which would relieve any financial burden and also help off-set the rising cost of paper that Burton needed to write and illustrate her stories. Burton did not accept money from her students, which proved inconsequential, as during those years she would publish her most famous works.

How it began though is perhaps not as important as how it all unfolded, and the processes to which the group came to be professionals. Initially, the work inspired social connections and companionship from the more mundane routines of daily life such as child-rearing and housework. It was an opportunity for women to have a creative outlet and learn a new skill. Yet over time, the group’s design and craft skills would become revered, which allowed several members to advance economically and become a key financial contributor in their household.

Image left: Burton, Clarke, L. Kenyon, H. Beatty, and I. Bruno. Photo for Life Magazine by Harold Carter, Sept. 19, 1945. Source: Cape Ann Museum.

Image right: Aino Clarke demonstrates jumping on a block for printing. Photo: Gerda Peterich. Source: Cape Ann Museum

Part of their success may be the way the group was organized, similar to a Medieval Guild. To be a candidate for official membership, one had to complete Demetrios’ design course, which required intensive hands-on training and homework. Once graduated, the candidate had to create a design that was presented to a five-person jury, made up of the most senior members on a rotating basis.

The jury would deliberate on the design, and offer artistic direction and advice. Once a design was approved, members carved their designs to a linoleum block, a process involving up to one hundred hours of labor. Designs were then transferred onto fabric using printer’s ink and by jumping on the block.

Image: Virginia Lee Burton Demetrios, The Making of a Block Print, date unknown. Source: Cape Ann Museum

To gain a real sense of the process, we can look at Demetrios’ design The Making of a Block Print, which illustrates the work of an aspiring member from concept to creation. From top left, the figure shows the struggle to conceptualize a design which moves into the moment when the image/idea becomes realized. Next comes the sketching of the design, the tedious and delicate task of carving the design onto the block, the selection of ink, and finally the transfer of the print onto fabric by jumping or “stamping.” The reiteration of these performances becomes pronounced as the fabric is woven within and around the entire image, blurring the ideas of start to finish - beginning to end. The fabric also illustrates how the tools and materials used become an intimate part of the process - a performance in unison. This entire task is no doubt a labor of LOVE (cleverly spelled backwards on the early part of the fabric). Demetrios fittingly used this design as the FCD “diploma” for graduating students of her design course.

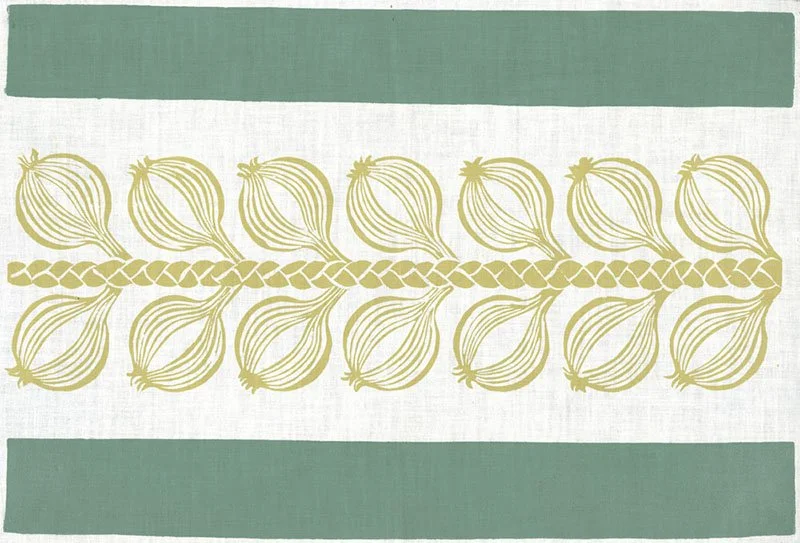

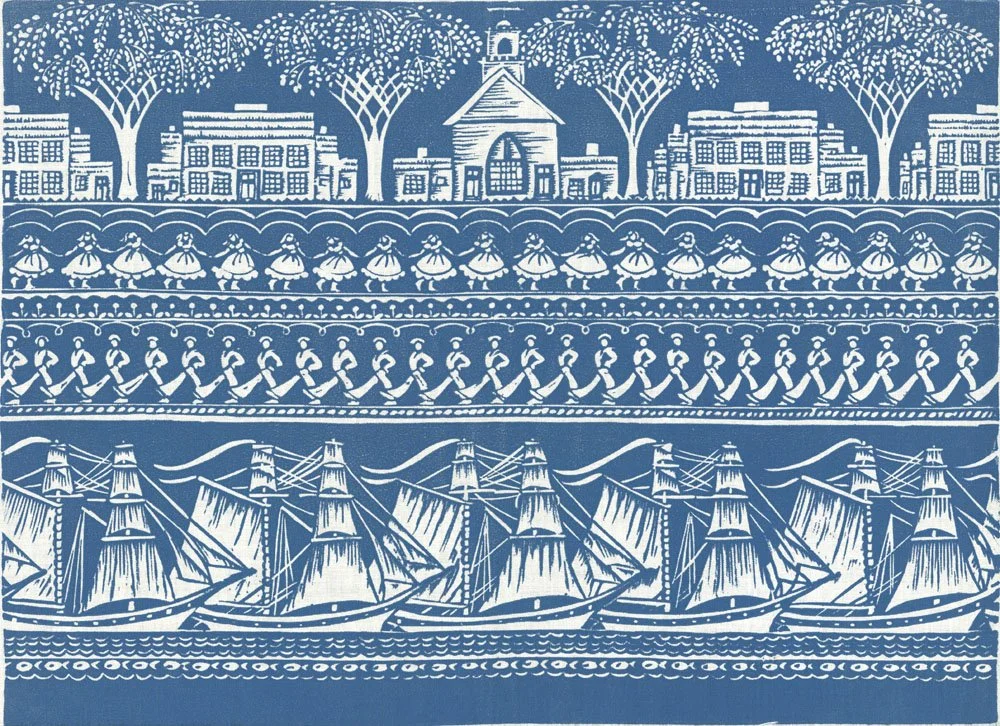

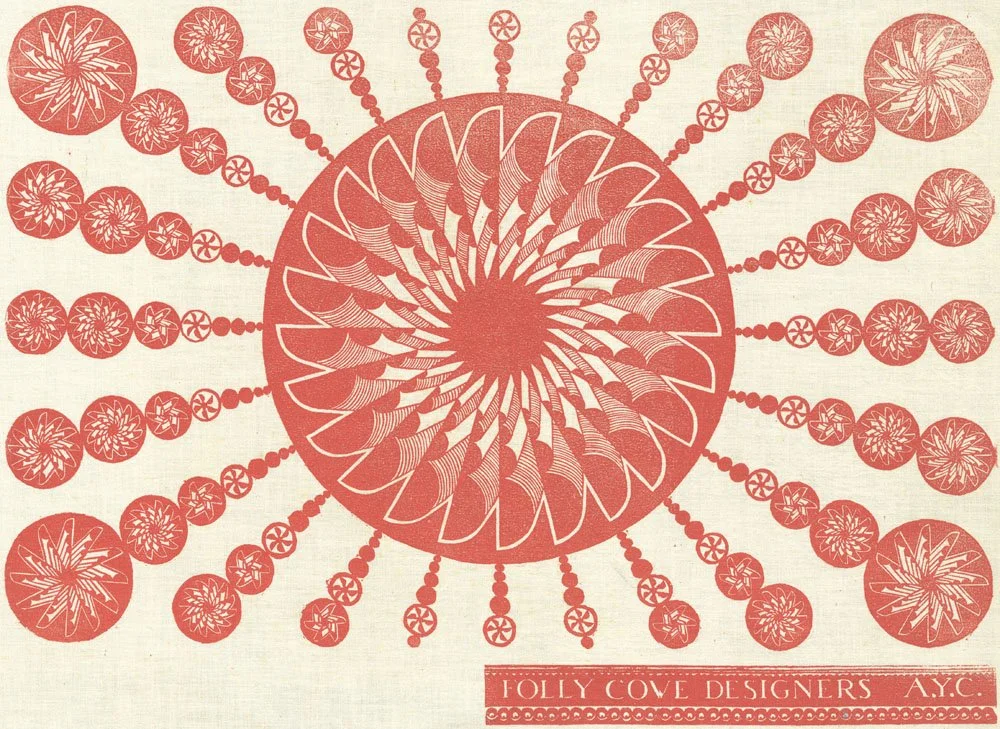

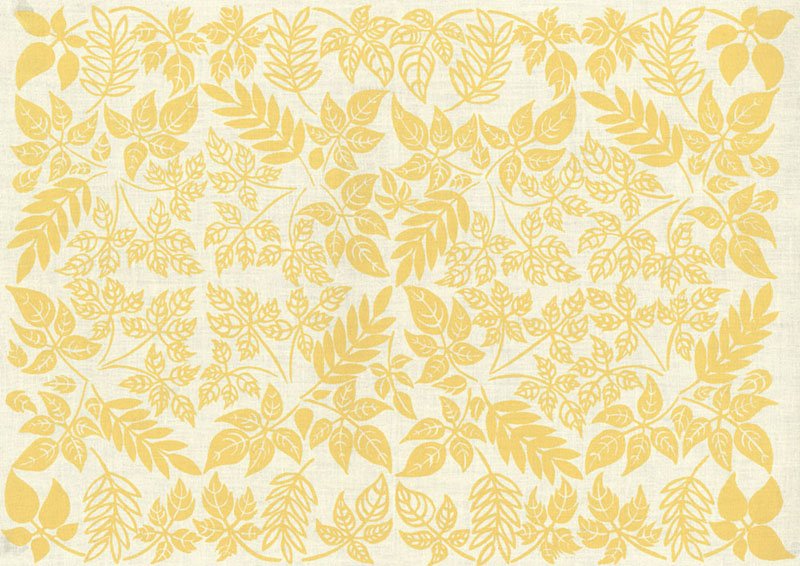

Burton asked her students to use Folly Cove as inspiration, draw from "what they knew,'' and sketch their subject over and over again until they “made them their own.” Through the years designs reflected ideas about gender, immigrant life, nature, and community. When the group organized professionally under Burton in 1941, the decision to work under the name Folly Cove Designers was a direct homage to the place they turned to for inspiration and the camaraderie they formed as local artisans. While men joined the group as artists and designers through the years and contributed some of the finest designs for the group, it was the women who established the foundation for the artistic process and formed the business for selling their goods. The FCD would go on to produce textiles and fabrics for Lord & Taylor, Schumacher, and American House (a retail outlet for national crafts) who celebrated their innovative designs. Despite their newfound acclaim, the group was intent on retaining the integrity of their communal craftsmanship. After Demetrios’ death in 1968, the artisans dissolved the FCD the following year.

The women of the FCD, as artists and laborers, became part of a socially and culturally engaged practice. In other words, the process of becoming a professional artisan and designer, was a consciousness-raising process (or artistic awakening if you will) for these women and an expression of communal ethos in which inclusivity and individual artistic expression was celebrated. They established a community that was founded on collective production, empowering each other both creatively and conceptually. They drew on tradition, repetition, and the transfer of artistic knowledge. The focus was on the work, the output, and every member contributed. Together these female craft artists created a legacy that still has yet to be fully realized within the history of the Arts and Crafts movement in twentieth-century America.

Folly Cove Designers, Select Textiles